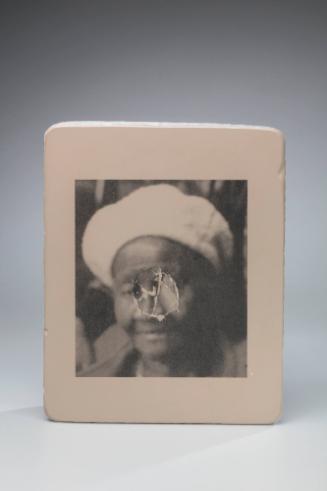

Gwen Knight

Gwen Knight

American, 1913 - 2005

Knight enrolled at Howard University and decided to pursue an art degree. She encountered professors like Loïs Mailou Jones, one of the few Black women painters that had visibility during this period, who was an important supporter of the young artist’s practice. With the onset of the Depression, however, Knight had to withdraw due to financial hardship. She returned to New York and found herself in the middle of the potent cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance. As Knight recalled, “It was a vital time; and, if it had not been for the rich environment, I would not have created as I did.”[2] But she also said of the Harlem Renaissance, “They were mostly interested in the men, we were ignored. They did not pay attention to us.”[3] A fellow residential boarder took Knight to visit the studio of renowned sculptor Augusta Savage (b. 1892, Green Cove Springs, FL—d. 1962, New York, NY); like with many young, Black artists, Savage quickly took Knight under her wing, mentored her, and fostered her artistic practice. On meeting Savage, Knight explains, “in 1939 there was an instant wonderful peace when I went to her studio. I felt included and embraced. It was she who told me I was an artist and encouraged me to do my art.”[4] The artist also spent a lot of time visiting museums and galleries for inspiration.

As part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) commissioned artistic projects throughout the country, employing many now celebrated artists; Knight also participated in these projects, such as managing the Harlem Hospital Mural Project supervised by artist Charles Alston, who apparently introduced her to Jacob Lawrence. She also took art classes at Harlem Community Art Center where some indicate is where she connected with a young Lawrence. Knight stated, “I liked his paintings and he had a gentleness about him.”[5] She would travel with Lawrence for his numerous projects and teaching opportunities and finally settled in Seattle when Lawrence received a teaching position at the University of Washington. During this time, Knight would continue to work and when in Seattle, one of Lawrence’s colleagues, Michael Spafford, introduced her to Francine Seder, a local gallerist who began working with her in the 1970s, and soon after Knight began exhibiting more broadly. Along with the Brandywine Museum and encouragement from Elizabeth Spafford, Michael Spafford’s partner, to create prints, Knight was able to produce a larger body of work to share with a greater public.

Gwendolyn Knight was the subject of the retrospective exhibition Never Late for Heaven: The Art of Gwen Knight, organized by the Tacoma Art Museum in 2003 that was accompanied by a monograph with the same title. She was featured in the exhibition, Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman, that began at the Cummer Museum, FL, in 2018, which traveled to the New York Historical Society, NY, the Palmer Museum of Art, PA, and the Dixon Gallery & Gardens, TN. The Black Mountain College Museum & Arts Center in North Carolina also featured Knight’s paintings and prints in the exhibition, Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, which was on view from 2018-2019. Knight’s work is represented in museum collections across the country, including the Amistad Research Center, LA; Hampton University Museum, VA; Minneapolis Institute of Art, MN; the Museum of Modern Art, NY; The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; Seattle Art Museum, WA; the Studio Museum, NY; Tacoma Art Museum, WA; and the Yale University Art Gallery, CT, amongst others.

[1] Redmond, “Gwendolyn Knight,” 11.

[2] Ibid, 9.

[3] Ibid, 9.

[4] Ibid, 14.

[5] Ibid, 16.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- Female

- Black American

Membership

Become a TMA member today

Support TMA

Help support the TMA mission